Earlier this month, hackers attacked Twitter. They gained access to up to 130 accounts, including prominent figures like Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and Joe Biden. Just over two weeks later, three suspected criminals were arrested for the crime.

Cybercriminals are rarely caught. So much so that Third Way estimates only 0.05% of cybercrimes result in conviction. This is a horrible number, but after spending over a decade fighting online abuse and fraud, it’s also in line with my expectations.

Essentially, if a criminal really wants to get away with cybercrime, he can.

How, then, were these ones caught in just over two weeks? That’s the question I’ll try to answer.

How big was the attack?

The attackers then tweeted out a scam requesting donations. This generated a little over $110,000 for the hackers.

The cost of this attack, of course, is much greater than that, though it’s hard to measure. Twitter is expending substantial resources responding, and their brand has taken a hit as people trust it less. These were very prominent accounts that were targeted, which generated unusual attention for an attack of this scale.

Twitter’s stock was trending down 3% the evening of the attack and then was down 7% before the market opened the following day. That would indicate a cost as high as $2 billion. But the stock was only down 1% by the end of the day, which would indicate a cost of around $300 million.

It’s hard to know what the stock would have done without the attack, so this is not a reliable measurement. Either way, it’s safe to say the cost is orders of magnitude more than the $110,000 the scammers obtained.

Only one in six cybercrime cases are even reported, so this being such a mainstream attack brings the likelihood of being caught up from 0.05% to 0.31%. Its prominence likely also increased the attention paid by authorities, which is hard to measure the impact of.

In this case, the FBI, U.S. Department of Justice, and authorities in California and Florida all cooperated to solve this crime. The prominence of the attack certainly helped get so many disparate authorities working together quickly on the case.

Were they caught by tracking their phone?

We don’t yet have the full details on how the authorities identified the perpetrators. We do have some details.

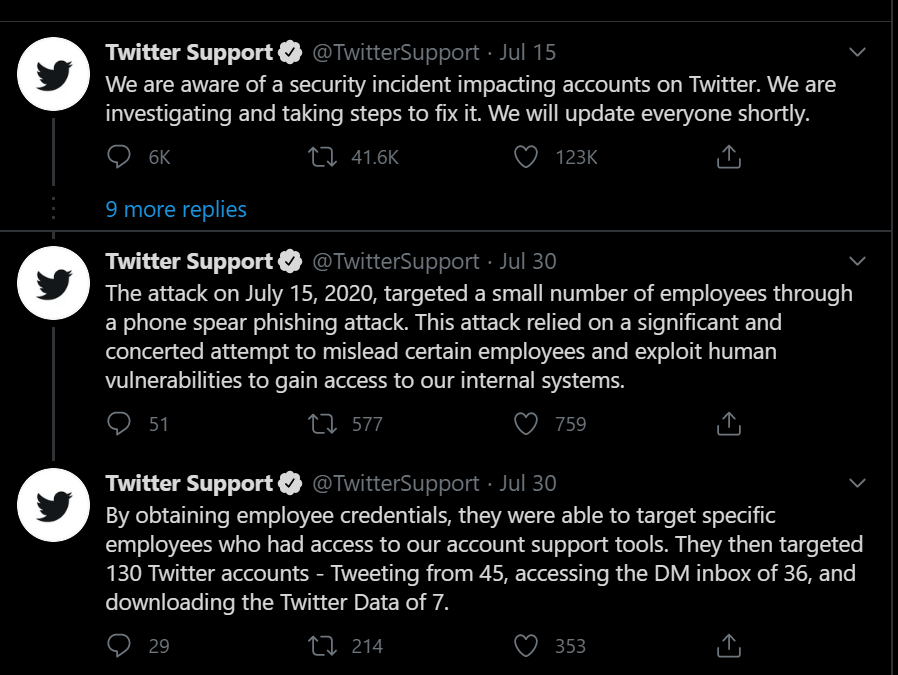

As is relatively standard in targeted attacks on high-profile victims, the attackers tricked Twitter’s support team into helping them take over these accounts. Support teams need to be able to access accounts to help legitimate users who have issues with their accounts, so if misused the tools they use could be used to hand control over to an attacker.

In this case, the perpetrators actually called Twitter support personnel on the phone, as reported by Twitter:

Did the authorities catch them by looking at the call logs of Twitter support engineers and tracking it back to the attackers that way? It’s unlikely, but possible. Smart attackers would use various techniques, such as online calling services or burner phones paid for with cash, rather than a personal phone that is easily traced.

Still, even these techniques leave authorities some ways to track the criminals: security footage at the store the burner phone was bought, logs at the Internet phone provider that indicate where the usage was coming from, etc.

The criminals likely carried out the attack by calling Twitter support personnel privately, rather than on a recorded call, though such a recording could also be a way to identify the criminals if they weren’t masking their voices.

They obtained the phone numbers somehow. Perhaps they found Twitter support personnel on LinkedIn and started a messaging conversation, creating fake accounts representing work colleagues and obtaining their phone numbers by tricking them via private messages.

In this scenario, if LinkedIn kept track of where the messages came from they could be used to track the criminals down. There are, of course, also ways for criminals to hide their digital tracks here as well.

Were they caught by following the money?

The scammers got the money in the form of Bitcoins, which are notoriously difficult to trace. But it’s not impossible.

Reports indicate that the criminals have attempted to hide the money as they route it through mixers intended to make it difficult to trace them, and the criminals have only extracted around 2% of the money so far.

Some of it went to a casino. This is a way for cybercriminals to launder the money, making it harder to trace. They could have used the bitcoins to deposit the money into an online casino account, gambled a little, and then turned around and extracted it into a more usable form of money by transferring it to their bank account—or back to bitcoin in a different account, making further tracking difficult.

This could work. However, if the casino keeps track of where the money comes in and goes out, authorities can still use this to track the money to its next destination, potentially including identifying the criminals. It appears they only transferred small quantities of money at a time in an attempt to avoid government reporting requirements. Still, this could be how they did it.

We don’t have details on the particular techniques law enforcement used to track the criminals, so providing a full cause is speculation. That said, there is one reason that’s highly likely to be true.

They were caught because they’re American

Most cybercriminals hide in Russia, China, Brazil, or other countries that don’t enforce cybercrime laws or cooperate with foreign governments trying to enforce theirs.

In this case, three Americans were charged with hacking into an American company. The attack was carried out here. The criminals connected to the Internet in America, and targeted a service in America.

While they certainly could have used obfuscation techniques, including VPNs to make it look like they were coming from Russia, or a bitcoin exchange overseas, they were physically in America. Their victim was a company also in America. If they took money out, it presumably would have been to use in America.

Living in the right home country is the best way to avoid detection

The biggest challenge in tracking down cybercriminals is where they come from. It is impossible to gain cooperation from some foreign countries, and the smart criminals and those who treat it as a profession generally live there.

It’s no surprise that when many of these crimes are actually solved, the criminal is in a Western country, and in many instances an overconfident teenager. In this case, it’s a teenager in America. In other cases, it’s Britain. Or in Spain. Or criminals in the Netherlands identified by British authorities. Or a criminal in Britain identified by German authorities.

Russians do get caught for their cybercrime. When they’re in Thailand. Or when they visit Amsterdam. Or on vacation in Spain.

Or in Prague, where Russians also accused him of cybercrime and requested extradition to prevent America getting its hands on him. That failed.

Or when visiting Israel. In this case, Russian authorities even went so far as to arrest an Israeli woman in an attempt to trade prisoners and avoid that criminal being extradited to America for prosecution. That attempt failed.

In other words, cybercriminals living in a country that harbors them shouldn’t go on vacation. And cybercriminals like the ones who perpetrated this Twitter hack probably would have gotten away with it if they lived in one of these havens.

Fortunately, this is one of the relatively rare cases where the criminal was in a country that takes protecting people from cybercrime seriously. If we’re ever going to get cybercrime under control, every country on the Internet has to do the same. Whether they do so willingly, or whether we have to remove their connections to the Internet to protect everyone else on the web.